Going through pictures last weekend with my husband, my son and daughter-in-law, I came across this one with a hole.

“Look at this. My dad is cut out of the picture,” I said.

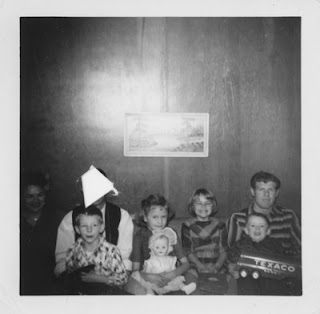

But what struck me before I said anything: I didn’t know I had a picture of the doll—the doll they buried with my sister. She died seventeen days after her seventh birthday, four days after this picture was taken.

I wrote about that nebulous memory in one of my Door essays, “The Duck and the Doll,” an inchoate creative writing assignment for a class at DTS. Stunned to see a picture of Renée holding the doll she had gotten for Christmas—the day this picture was taken—the glossy black and white image refreshed my shame. I had asked for her doll when she died because my gift was a cradle without a doll.

But back to the picture with a hole.

A wistful feeling swept over me that my dad was missing. He died, too, not quite three months later. It would have been the only picture I have of the four of us together before they died: my mom, my dad, Renée and me. Unc, on the far right next to me, died in 1992. The two boys are cousins, Joe and Mike. Auntie, my mother’s younger sister, took the picture.

My mother, who died in 1998, said she hated pictures. Few of her pictures have ended up in my possession—these timeless-ageless mementos that root me to a reality lived through while their substance remains as murky and fluid as a river.

My daughter-in-law held the picture in her hand to examine it. “My mom cut my dad out of pictures after their divorce.”

We all agreed that my mom had to have cut my dad out of the picture.

“Who knows why?” I added. “Maybe Mom blamed him for Renée's death.”

Still the picture itself bore evidence to the memory that caused me to swallow hard and fight the tears. Keep sorting, I told myself. Forget about the doll. Forget about the duck. Forget about the dad.

The next morning, on our way home, my husband and I pulled into a Sonic in Amarillo. The crate full of pictures I had carted on this trip sat behind my seat; I kept thinking about one picture with a hole.

“I cut the picture.”

My husband said, “What are you talking about?”

“I remember a gold-plated locket that I wore. I don’t remember who gave it to me or when, but it’s coming back to me. I cut the picture of my dad’s face out and put it in that locket.” The memory came to me as if I had floated through fog, an unsubstantial spirit seeking rest.

“That makes sense,” he said.

Yes, the sharp angles of the cuts in the picture—it looks like I used a knife instead of scissors—imprecise cuts. The extracted piece would have revealed a tiny image of my handsome dad, a piece of my story to wedge in a cheap locket.

On the back of the picture with the missing daddy, my mother wrote, “Gone so soon!”

And I think, "Gone for so long."

1 comment:

When I read your writings about your childhood and past, I feel like I keep getting pieces to the puzzle that is you. Some are new, but some are pieces I've had, forgotten, then remembered again through your stories. It's a bit of the past that is preserved each time you write. I love and cherish it!

Post a Comment